After all the picking, and

the rehearsal in London earlier in the month, the last six days have been full-on on apples at the Wisley Taste of Autumn Festival and one can get enough of apples, I tell you!

|

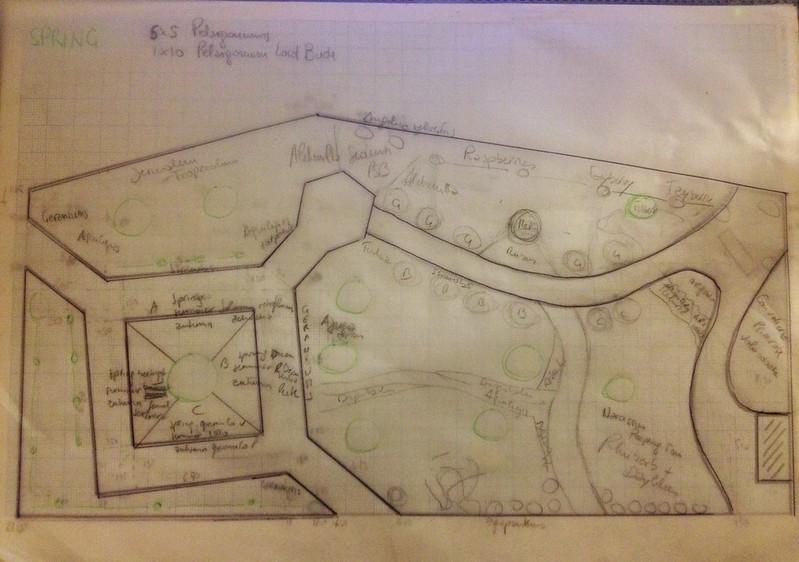

| Produce display for Wisley Taste of Autumn |

After a day of set up that involved me checking stored crates of apples and pears for rotting ones to discard, and making an apple mosaic in the lovely autumnal display that we created in front of our stand, we set out to display tasters of our produce so that the public could appreciate a wider variety of apples, and to sell our apples and pear to help with our budget.

October is a special month for apples: for one they are around, but also, since 1990,

the Orchard Network has promoted the institution of Apple Day to bring back traditional orchards from abandon, and to celebrate the variety of apples that small scale, local production entails.

And here we grow some 750 varieties of apples (eaters and cookers) and 150 of pears: both modern and traditional varieties, some of which date back to when the National Fruit Collection was located at Wisley in the 1920s: a joy to the palate!

In fact, apples do come in an amazing variety of flavours and textures, as I have learned over the last week, tasting them to help customers with their choices and to encourage tentative attempts at trying something new.

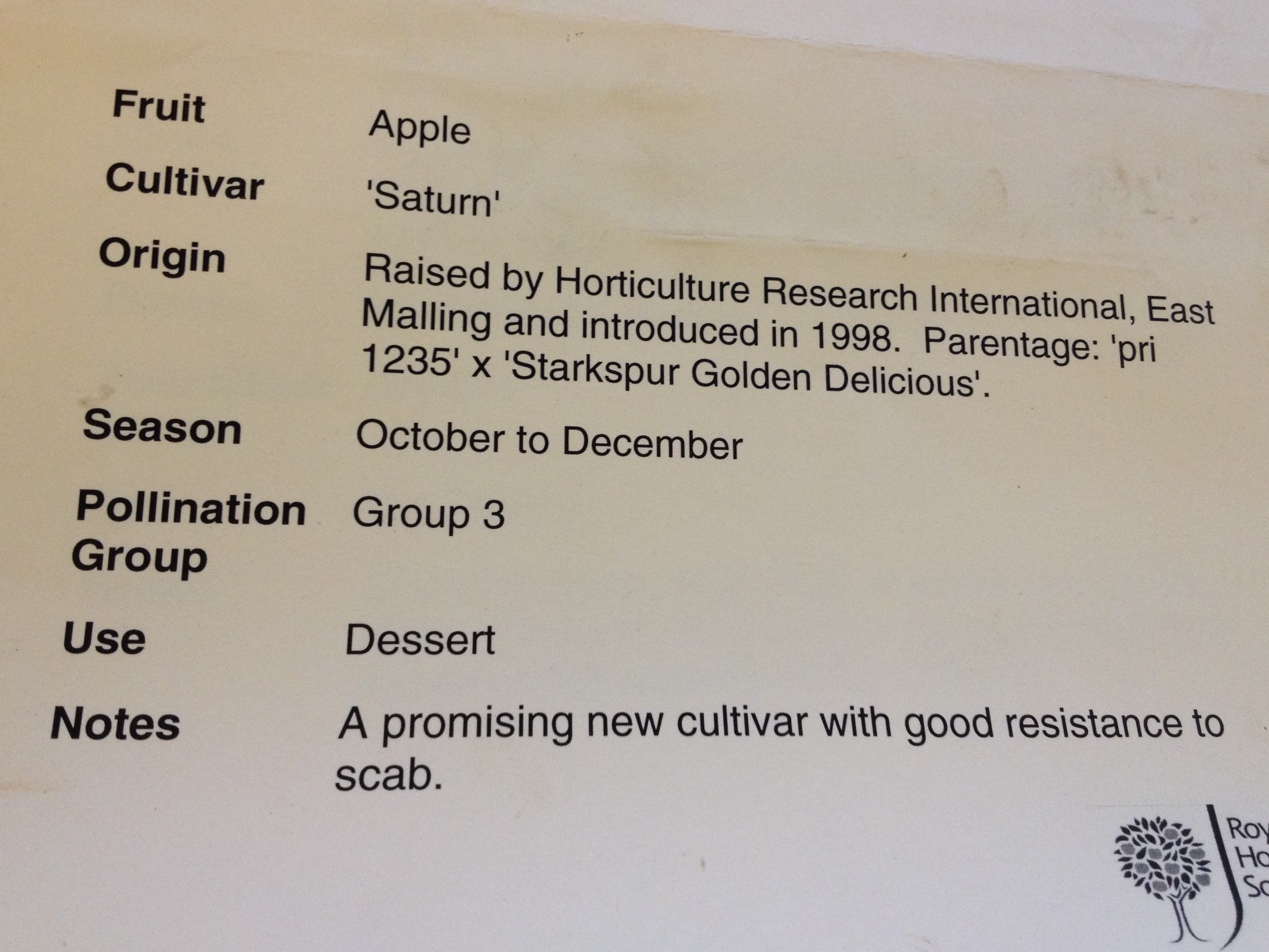

You get the whole spectrum from soft through floury to crunchy and all the in-betweens; juicy to dry; and sweet through fruity, to sharp to acidic. Amazing. And the strangest apple I tasted I was not able to describe, even after repeated tasting. It was called

'Saturn': floury in texture, with an aniseed note, it was almost savoury rather than sweet.

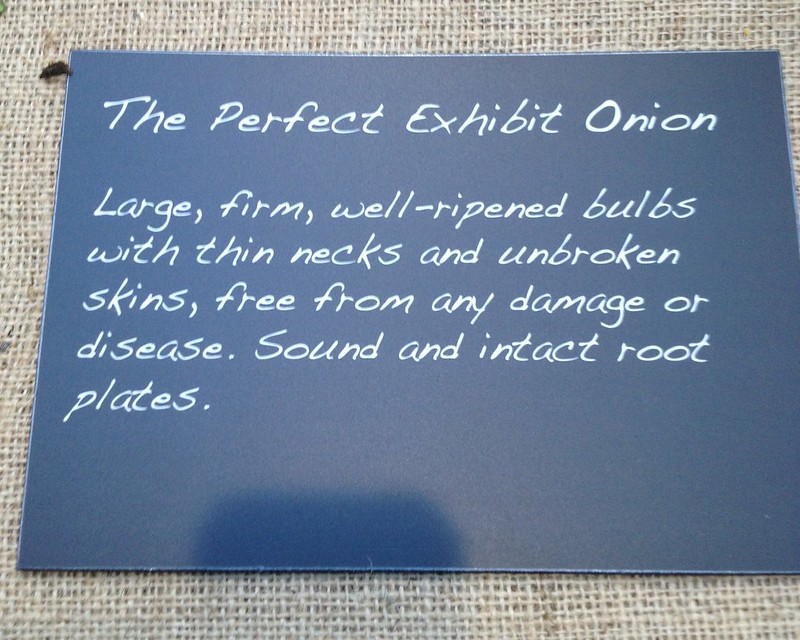

What was most interesting was to observe the reactions of people visiting us to the look and taste of the apples.

Several people dismissed apples only on their looks (which have generally little to do with either flavour or nutrition) - at some point, we had quite a tasty russeted apple, and I had to tell people: ignore their look and delight in their taste - they would have otherwise been completely ignored. Some actually said they would not expect such a good flavour in an unappealing apple. That is obviously going to be a problem for anyone who wants to market tasty produce that is not grown to supermarket plastic-fantastic standard. I was really surprised by seeing this in practice, although I had read about it profusely.

And I am not sure people realise what are the costs of such shining perfect appearance of the produce they would go for. First of all, for the producers and food waste, as crops that are perfectly edible and nutritious may be rejected by supermarkets, throwing farmers into financial distress (sometimes disaster) and often ending up in the compost heap themselves

(as even ITV found out). But also, that search for the perfect look pushes suppliers to treat fruits, that come from further and further away and are stored for longer and longer to be available all year round, with all sorts of chemical and physical treatments (from

gamma rays in Egypt to

chemicals raising health concerns in the US).

|

| Water core in 'Golden Pearmain' |

An interesting example was apples with

water core, a disorder that causes areas of the apple to be flooded with sorbitol (that is not converted to fructose) and become translucent. While not completely understood, water core is thought to be related to ripening, contributing factors including excess of nitrogen associated to low calcium, and temperature variations.

We got a cultivar called

'Golden Pearmain' that seemed subject to it, and my colleagues all wanted a taste, as it is quite sweet, thanks to the sorbitol. In Japan, 'honeyed apples' with water core fetch higher prices and the famous '

Fuji' cultivar bred there is susceptible*.

Visitors at the Festival, however, shunned the plate, at least until I explained why the look of the apple was different. Would I have done the same? I had never known the disorder myself, and that is because commercially sold apples are screened for it with a variety of non-destructive techniques: light transmission, mass density sorting, MRI, CT scans and thermal imaging*... talking of keeping the doctor away!

After five days, I decided my greatest pleasure was seeing some kids and the odd adult just taste all the apples on offer, trying to discern the different flavours, rather than judge and dismiss them quickly, or favourite them. And it was a real pleasure to see so many kids so keen on fresh fruit for once: are apples the way into the heart of future healthy eaters? It is true that the demographics that visited Wisley for the Festival were likely not average of the general public...

* Sources:

Michigan State University Apples Extension, Water core in apples, http://apples.msu.edu/uploads/files/Watercore_in_apples.pdf

NSW Dept of Primary Industries http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/40084/Watercore_of_apples-primefact49.pdf